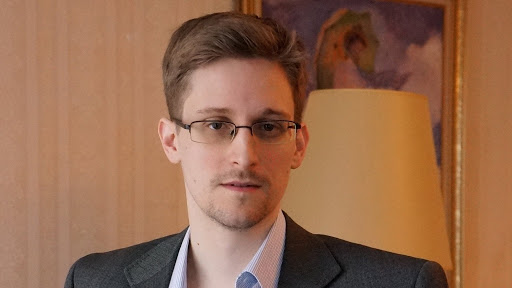

Edward Snowden

~ A simple explanation on how blockchain works

Snowden has worked in the American espionage service at the NSA and CIA. He leaked secret data to Glenn Greenwald, who was a journalist at the British magazine, The Guardian, and in 2013 he publishes all the data obtained from Snowden. In the present Snowden is tracked by the CIA being accused of high treason. Being a refugee in Hong Kong he leaves china in 23 July 2013. He traveled to Russia and settled in the transit area of Sheremetyevo Airport. He hired a Russian lawyer, Anatoly Kucherena, and sought political asylum in more than 20 countries. After more than 1 month and 1 week, he received political asylum from Russia for 1 year, but also extended his stay until 2020.

It’s basically just a new kind of database.

Imagine updates are always added to the end of it instead of messing with the old, preexisting entries — just as you could add new links to an old chain to make it longer — and you’re on the right track. Start with that concept, and we’ll fill in the details as we go.

Imagine an old database where any entry can be changed just by typing over it and clicking save. Now imagine that entry holds your bank balance. If somebody can just arbitrarily change your balance to zero, that kind of sucks, right? Unless you’ve got student loans. The point is that any time a system lets somebody change the history with a keystroke, you have no choice but to trust a huge number of people to be both perfectly good and competent, and humanity doesn’t have a great track record of that.

Blockchains are an effort to create a history that can’t be manipulated. Transactions.

In its oldest and best-known conception, we’re talking about Bitcoin, a new form of money. But in the last few months, we’ve seen efforts to put together all kind of records in these histories. Anything that needs to be memorialized and immutable. Health-care records, for example, but also deeds and contracts. When you think about it at its most basic technological level, a blockchain is just a fancy way of time-stamping things in a manner that you can prove to posterity hasn’t been tampered with after the fact.

The very first bitcoin ever created, the “Genesis Block”, famously has one of those “general attestations” attached to it, which you can still view today. It was a cypherpunk take on the old practice of taking a selfie with the day’s newspaper, to prove this new bitcoin blockchain hadn’t secretly been created months or years earlier (which would have let the creator give himself an unfair advantage in a kind of lottery we’ll discuss later).

Some of that is hype cycle.

Look, the reality is blockchains can theoretically be applied in many ways, but it’s important to understand that mechanically, we’re discussing a very, very simple concept, and therefore the applications are all variations on a single theme: verifiable accounting.

So, databases, remember? The concept is to bundle up little packets of data, and that can be anything. Transaction records, if we’re talking about money, but just as easily blog posts, cat pictures, download links, or even moves in the world’s most over-engineered game of chess.

Then, we stamp these records in a complicated way that I’m happy to explain despite protest, but if you’re afraid of math, you can think of this as the high-tech version of a public notary.

Finally, we distribute these freshly notarized records to members of the network, who verify them and update their independent copies of this new history. The purpose of this last step is basically to ensure no one person or small group can fudge the numbers, because too many people have copies of the original.

It’s this decentralization that some hope can provide a new lever to unseat today’s status quo of censorship and entrenched monopolies.

About monopolies

Imagine that instead of today’s world, where publicly important data is often held exclusively at GenericCorp LLC, which can and does play God with it at the public’s expense, it’s in a thousand places with a hundred jurisdictions. There is no takedown mechanism or other “let’s be evil” button, and creating one requires a global consensus of, generally, at least 51 percent of the network in support of changing the rules.

Let’s pretend you’re allergic to finance, and start with the example of an imaginary blockchain of blog posts instead of going to the normal Bitcoin examples. The interesting mathematical property of blockchains, as mentioned earlier, is their general immutability a very short time past the point of initial publication.

For simplicity’s sake, think of each new article published as representing a “block” extending this blockchain. Each time you push out a new article, you are adding another link to the chain itself. Even if it’s a correction or update to an old article, it goes on the end of the chain, erasing nothing. If your chief concerns were manipulation or censorship, this means once it’s up, it’s up. It is practically impossible to remove an earlier block from the chain without also destroying every block that was created after that point and convincing everyone else in the network to agree that your alternate version of the history is the correct one.

Let’s take a second and get into the reasons for why that’s hard. So, blockchains are record-keeping backed by fancy math. Great. But what does that mean? What actually stops you from adding a new block somewhere other than the end of the chain? Or changing one of the links that’s already there? We need to be able to crystallize the things we’re trying to account for: typically a record, a timestamp, and some sort of proof of authenticity.

So on the technical level, a blockchain works by taking the data of the new block — the next link in the chain — stamping it with the mathematic equivalent of a photograph of the block immediately preceding it and a timestamp (to establish chronological order of publication), then “hashing it all together” in a way that proves the block qualifies for addition to the chain.

Hash Function

A cryptographic hash function is basically just a math problem that transforms any data you throw at it in a predictable way. Any time you feed a hash function a particular cat picture, you will always, always get the same number as the result. We call that result the “hash” of that picture, and feeding the cat picture into that math problem “hashing” the picture. The key concept to understand is that if you give the very same hash function a slightly different cat picture, or the same cat picture with even the tiniest modification, you will get a WILDLY different number (“hash”) as the result.

So we hash these different blocks, which, if you recall, are just glorified database updates regarding financial transactions, web links, medical records, or whatever. Each new block added to the chain is identified and validated by its hash, which was produced from data that intentionally includes the hash of the block before it. This unbroken chain leads all the way back to the very first block, which is what gives it the name.

What is money?

The same one it solves everywhere else: trust. Without getting too abstract: what is money today? A little cotton paper at best, right? But most of the time, it’s just that entry in a database. Some bank says you’ve got three hundred rupees today, and you really hope they say the same or better tomorrow. Now think about access to that reliable bank balance — that magical number floating in the database — as something that can’t be taken for granted, but is instead transient. You’re one of the world’s unbanked people. Maybe you don’t meet the requirements to have an account. Maybe banks are unreliable where you live, or, as happened in Cyprus not too long ago, they decided to seize people’s savings to bail themselves out. Or maybe the money itself is unsound, as in Venezuela or Zimbabwe, and your balance from yesterday that could’ve bought a house isn’t worth a cup of coffee today.

Monetary systems fail!

What makes a little piece of green paper worth anything? If you’re not cynical enough to say “men with guns,” which are the reason legal tender is treated different from Monopoly money, you’re talking about scarcity and shared belief in the usefulness of the currency as a store of value or a means of exchange. Let’s step outside of paper currencies, which have no fundamental value, to a more difficult case: why is gold worth so much more than its limited but real practical uses in industry? Because people generally agree it’s worth more than its practical value. That’s really it. The social belief that it’s expensive to dig out of the ground and put on a shelf, along with the expectation that others are also likely to value it, transforms a boring metal into the world’s oldest store of value.

Blockchain-based cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin have very limited fundamental value: at most, it’s a token that lets you save data into the blocks of their respective blockchains, forcing everybody participating in that blockchain to keep a copy of it for you. But the scarcity of at least some cryptocurrencies is very real: as of today, no more than twenty-one million bitcoins will ever be created, and seventeen million have already been claimed. Competition to “mine” the remaining few involves hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of equipment and electricity, which economists like to claim are what really “backs” Bitcoin. Yet the hard truth is that the only thing that gives cryptocurrencies value is the belief of a large population in their usefulness as a means of exchange.

That belief is how cryptocurrencies move enormous amounts of money across the world electronically, without the involvement of banks, every single day. One day capital-B Bitcoin will be gone, but as long as there are people out there who want to be able to move money without banks, cryptocurrencies are likely to be valued. I like Bitcoin transactions in that they are impartial.

They can’t really be stopped or reversed, without the explicit, voluntary participation by the people involved.

Let’s say Bank of America doesn’t want to process a payment for someone like me. In the old financial system, they’ve got an enormous amount of clout, as do their peers, and can make that happen. If a teenager in Venezuela wants to get paid in a hard currency for a web development gig they did for someone in Paris, something prohibited by local currency controls, cryptocurrencies can make it possible. Bitcoin may not yet really be private money, but it is the first “free” money. Bitcoin has competitors as well. One project, called Monero, tries to make transactions harder to track by playing a little shell game each time anybody spends money. A newer one by academics, called Zcash, uses novel math to enable truly private transactions.

If we don’t have private transactions by default within five years, it’ll be because of law, not technology.

Proof of work / Proof of stake

Suffice it to say cryptocurrencies are normally implemented today through one of two kinds of lottery systems, called “proof of work” and “proof of stake,” which are a sort of necessary evil arising from how they secure their systems against attack. Neither is great. “Proof of work” rewards those who can afford the most infrastructure and consume the most energy, which is destructive and slants the game in favor of the rich.

“Proof of stake” tries to cut out the environmental harm by just giving up and handing the rich the reward directly, and hoping their limitless, rent-seeking greed will keep the lights on. Needless to say, new models are needed.

Okay, imagine you decide to get into “mining” bitcoins. You know there are a limited number of them up for grabs, but they’re coming from somewhere, right? And it’s true: new bitcoins will still continue to be created every ten minutes for the next couple years. In an attempt to hand them out fairly, the original creator of Bitcoin devised an extraordinarily clever scheme: a kind of global math contest. The winner of each roughly ten-minute round gets that round’s reward: a little treasure chest of brand new, never-used bitcoins, created from the answer you came up with to that round’s math problem.

To keep all the coins in the lottery from being won too quickly, the difficulty of the next math problem is increased based on how quickly the last few were solved. This mechanism is the explanation of how the rounds are always roughly ten minutes long, no matter how many players enter the competition. The flaw in all of this brilliance was the failure to account for Bitcoin becoming too successful. The reward for winning a round, once worth mere pennies, is now around one hundred thousand dollars, making it economically reasonable for people to divert enormous amounts of energy, and data centers full of computer equipment, toward the math — or “mining” — contest. Town-sized Godzillas of computation are being poured into this competition, ratcheting the difficulty of the problems beyond comprehension.

This means the biggest winners are those who can dedicate tens of millions of dollars to solving a never-ending series of problems with no meaning beyond mining bitcoins and making its blockchain harder to attack. The tech is the tech, and it’s basic. It’s the applications that matter.

How can it be used?

The real question is not “what is a blockchain,” but “how can it be used?”

And that gets back to what we started on: trust. We live in a world where everyone is lying about everything, with even ordinary teens on Instagram agonizing over how best to project a lifestyle they don’t actually have. People get different search results for the same query. Everything requires trust; at the same time nothing deserves it. This is the one interesting thing about blockchains: they might be that one tiny gear that lets us create systems you don’t have to trust.

You’ve learned the only thing about blockchains that matters: they’re boring, inefficient, and wasteful, but, if well designed, they’re practically impossible to tamper with. And in a world full of shifty bullshit, being able to prove something is true is a radical development.

Maybe it’s the value of your bank account, maybe it’s the provenance of your pair of Nikes, or maybe it’s your for-real-this-time permanent record in the principal’s office, but records are going to transform into chains we can’t easily break, even if they’re open for anyone in the world to look at. The hype is a world where everything can be tracked and verified. The question is whether it’s going to be voluntary.